A Mirrored Lantern

A Mirrored Lantern

It was twenty minutes into the power failure before Arthur finally decided to light a flame. It took that long for him to decide that it was a semi-permanent situation, find the faux pewter lantern and fill the base with oil. He set the lamp on an end table and stared into the light. His girlfriend, Allison, stared too.

“It’s pretty,” she said.

Arthur didn’t answer.

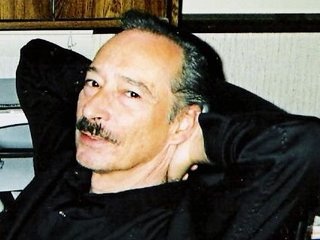

The glow was generally kind to him, giving a warm color to his skin that light bulbs and sunshine failed to do. But it was unkind as well, making the slight wrinkles around his eyes look deeper and old. Allison was twenty years younger and didn’t need the help, but her tan now took on an even more golden glow.

“I wish I had more than one lantern,” Arthur said. “We had a pair of them, but I don’t know where the other one is.” The “we” was Arthur and his ex-wife. Allison noted the “we” but didn’t care much and said nothing.

“I wonder,” said Arthur, “if I put a mirror behind it, if that would double the amount of light? It would have to, wouldn’t it? I mean, it would be like two flames.”

“I don’t know,” said Allison. She was wondering if the power was out at her apartment and how long the ice cream would stay frozen. She snuggled closer to Arthur and rested her hand on his thigh.

“Or if I had two mirrors, would it be like having three lights.”

“Oh, A. J.,” she said, “I don’t know. It couldn’t be, really. Then why would people ever have more than one lamp or candle or anything in a room? Don’t you suppose that even before people had electric lights, some one would have thought of that?” She brought her hand up higher on his leg.

“I think we have an old mirror in the garage,” he said. Arthur was forty-five, loved sex, and especially loved it now with Allison. But now was not the time. Later in the evening would be the time; after the power came back on, he could turn out the lights and they could go upstairs.

He stood up, took his weak little flashlight in his hand and opened the door in the family room that accessed the garage. He was back five minutes later. “Well, I thought we had one.”

“I think,” said Allison, “that all a mirror would do would be to catch the light that’s going the other way and bounce it back this way.”

“Still, wouldn’t that double the brightness?”

“Maybe,” she said. “Maybe it just returns the light that’s wasted on the wall. But still, there’s only so much light in one flame.”

Arthur sat back down. Allison sat straight, her hands folded in her lap, wondering if her cat was afraid of the dark. Probably not.